Introduction

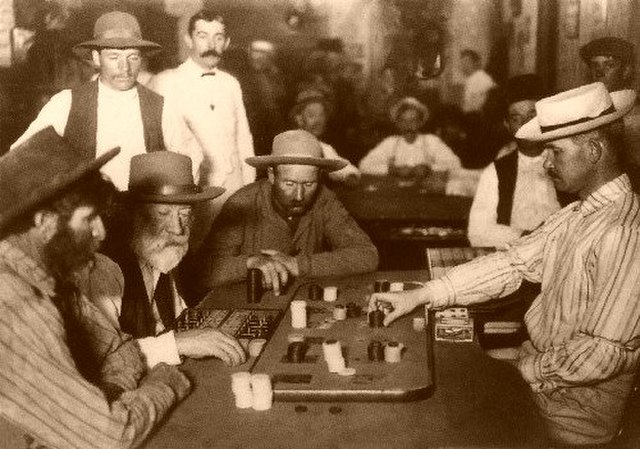

Faro was one of the most popular gambling games in early Tombstone and nearly anywhere else in the United States in the late 1800s. It was popular, undoubtedly, because it was effortless to learn, and players did not need any skill. The game was also very fast-paced, so players would have a constant rush of energy as they placed their bets. Finally, Faro has about the best odds for the player of any gambling game, so players would at least occasionally “win.”

Faro was often called “bucking the tiger” or “twisting the tiger’s tail” since the early card decks featured a drawing of a Bengal tiger. At one point, the game was so popular that saloons would advertise it with nothing more than a drawing of a tiger in the front window.

The Game

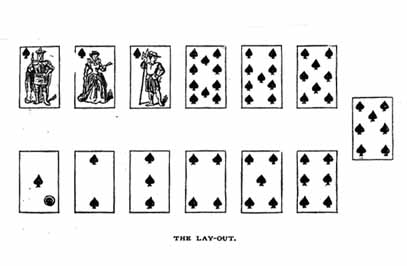

Faro was a game of chance between the “bank” (or house) and one or more “punters” (or players). It was played with a single deck of cards on an oval table with a layout of cards glued to its surface. Punters would bet by placing their “check” (a chip) on one of the cards. Then, the banker (dealer) would turn up two cards from the deck. The first was the “banker’s card,” and the banker kept any checks placed on that card. The second was the “player’s card,” and any checks placed on that card were increased by the banker one-for-one (even money) and retained by the punter. In Faro, the suit did not matter.

There were only a few exceptions to the play. The first card in a freshly shuffled deck was called the “soda” and discarded, leaving 51 cards. Also, the betting changed when only three cards remained in the deck. The banker would “call the turn,” and punters would bet on the exact order of the last three cards. The dealer’s card, player’s card, and final unused card (called the “hock”) would be turned, and players who correctly guessed the order of the last three cards won four-to-one.

A “casekeep” was used at the table to assist the punters. A casekeep was similar to an abacus, and someone (the “casekeeper,” or more colorfully, the “coffin driver”) would move a bead that indicated which card was displayed on every roll. This way, punters would know what cards had already been played and what remained in the deck.

There were two other special rules. Punters could place their check between two cards to play both at one time. Also, punters could place a “copper” (a penny) on top of their bet to indicate that they wanted to reverse the two cards, so the banker’s card became a winner while the player’s card was a loser. Like everything else about the game of Faro, these rules were easy to learn and apply.

Final Notes

Unfortunately, it was stunningly easy to cheat in Faro. The banker could manipulate the table to increase the odds for the house considerably. Even clever punters could cheat by moving their bets around on the table while the banker was distracted. Finally, the casekeeper, who was supposed to be independent of the banker, could work out an “under the table” arrangement that was very profitable for both men. Cheating in Faro was so prevalent that one edition of Hoyle’s Rules of Games warned that there was no single honest Faro game in the United States.

In the saloons around Tombstone, a Faro table would be noisy and exciting. A man could enter or exit a game at any time, and it did not matter how many were playing. For a miner who had a few dollars in his pocket, a Faro table was almost irresistible, and many men quickly lost their wages. At least one gunfight erupted over an accusation of cheating in Faro when Luke Short killed Charlie Storms in 1881. Faro was one of the most constant facets of early Tombstone.